The Jubilee Cross

The Jubilee Cross

at the Shrine of the Discalced Carmelites in Munster, IN

The Jubilee Cross (illustration 1) is a token of gratitude of our religious community for the 70th anniversary of its existence. It was precisely on January 17, 1950, that our friars received a decree from the Holy See establishing the foundation of our monastery, beginning in neighboring Hammond, but then moving to its present site in Munster in 1952.

We entrusted the building of the Cross to master carpenter Andrzej Jędzejczak; however, the artist Leszek Maćkowiak, who was trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznan, Poland, designed and carried out the project. Leszek Maćkowiak is an interior designer, painter, sculptor, gold finisher, and an expert in the field of conserving works of art.

The Jubilee Cross in its basic form is connected with the cross designed by the Italian artist Maestro del Bigallo (illustration 2). Our goal, however, was not to reproduce a faithful copy of that cross, but rather, based on the “Roman prototype”, to create a new work that would be especially suited to our shrine and connected to our Carmelite charism, as well as portray the distinctive character of this shrine.

The “Roman” Cross – a Prototype

The prototype of our Cross is located in the Palazzo Barberini, one of two sites of the National Gallery of Ancient Art in Rome. This museum holds one of the greatest collections of paintings from the 11th to the 16th centuries. In order to understand the symbolism of the new Cross, it seems reasonable, first of all, to analyze the work of the Florentine master, Maestro del Bigallo. Maestro del Bigallo was an anonymous Italian artist born in the first half of the 13th century, a master of the Florentine school, and named thus (the Master of Bigallo) from one of his works: the Crucifix in the Loggia Museum of Bigallo in Florence (illustration nr. 3).

It is worth mentioning that one of the crosses by this same artist, completed between the years 1255-1265, is found in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (illustration 4).

The “Roman crucifix” was painted around 1260-1270 (dimensions: 160 x 110 cm). It is numbered among those images of the Crucified Christ depicted in the convention of Christus Triumphans (Christ in triumph) which is related to the Byzantine tradition and is typical of earlier Western sacred art from the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. For this reason, we can still ascribe the work of art we are analyzing to the early Roman style of art.

In the later Gothic style of sacred art, another type of image occurred more frequently: “Christus Patiens” (the dying, suffering Christ), as a reflection of the Franciscan spirituality of the passion (illustrations 7-9).

We can assign this Cross to the genre of so-called mural painting, that is, an image designed to be set apart for exposition on a wall beyond the altar; for this reason, it is distinguished from so-called altar painting. The Cross was painted on wood with distempered paint and gold finishing typical of that period. Distempered painting is an artistic technique in which the oldest type of emulsifying pigment is applied, produced by combining dyes with the help of egg yolk, resin, or oil.

The Figure of Christ

The Figure of Christ, similar to the others depicted (Mary, St. John the Evangelist) is painted in the style typical of Roman art: a flat and linear image, without shading or perspective, with an outline around it and filled in with color (mainly gold, red, and blue). Christ, even though He is on the cross, is depicted as risen from the dead, glorified as the One who has conquered sin and death.

The Florentine master depicts the glorified Christ, and even though blood flows from his wounds, it is neither a sign of His passion nor His death, but above all, a theological symbol: The Most Precious Blood of Christ is the source of our life and immortality.

Christ has his eyes open. The tender, peaceful, and radiant face of Jesus appears even joyful, and does not bear the crown of thorns. The head of Jesus is surrounded with a golden halo, which emphasizes His divine nature (illustration 5).

From the Gospel of St. John, we know that “Pilate also wrote an inscription and ordered that it be put on the cross. And there was written: Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews… And it was written in Hebrew, in Greek and in Latin” (John 19:19-20). For this reason, above the figure of Jesus Crucified can be seen the Byzantine Christogram – the Greek letters: IC XC, referring to the Greek version of the name of the Savior: ΙΗΣΟΥΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ – Jesus Christ. A thick brushstroke caps the in-scription, reminding us that this is a Holy Name.

The sash on the hips (efod) emphasizes the royal and priestly dignity of Christ in the colors: white, light green, and gold, alluding to the lining on the garments of the priests of the Old Testament (illustration 10). Christ’s body is straightened out, in contrast to the Gothic style, in which His positioning recalls the letter “S” shape (illustrations 7-9). The feet, pierced with nails in a similar way as the hands, are not joined together, however, conveying the impression that Christ did not hang on the cross, but was standing. This is yet another typical quality of the image of Christus Triumphans.

The beams of the Cross are painted in a dark blue color, which (like green), symbolize the world and its history. This is a theological message referring to the words of St. Paul: “When the fullness of time came, God sent forth His Son, born of a Woman, born under the Law, to redeem those who had been subjected to the Law, that they might receive adoption as sons” (Gal 4:4-6).

The Incarnation was accomplished at a concrete time and place of our history and is an expres-sion of how the Son of God humbled Himself, He who “while existing in the form of God, did not deem equality with God, something to be grasped at, but emptied himself, taking on the form of a slave, becoming like men in all things. And while he was regarded as man in his external appearance, he humbled Himself, becoming obedient even unto death – death on a cross. Therefore, God exalted him above all things … so that every tongue might confess that Jesus Christ is LORD – to the glory of God the Father” (Phil 2:6-11).

The Composition and Ornamentation of the Cross

In describing the composition and individual sections of the Cross, we make use of the scheme drawn up by Italian historians of art (illustration 11). The vertical beam of the cross emerges from the “base” (piede) and is topped off with a “crown” (cimasa). In the extension of the cross-beam are placed two miniatures defined as “extensions” (terminale), and below (under the cross-beam of the Cross, on both sides of the vertical beam) are two “boards” (scomparto).

The individual elements of the Cross (the base, extensions, boards, and crown) are encom-passed by a red frame, in the background of which are placed circular ornaments made from pearl. This framing with a chain of pearls is meant to highlight the individual chapters from the entire narration of the Paschal Mystery, as described on the image of the Cross.

In ancient times, the pearl was a sign of love. It forms in a mussel as a result of the defensive reaction of the organism in the face of a foreign body, as “the fruit of suffering.” This was the reason why, for Christians, it often symbolized the sacrificial love of Christ; also, it is a symbol of the purity and nobility of Mary Immaculate.

The Crown (cimasa)

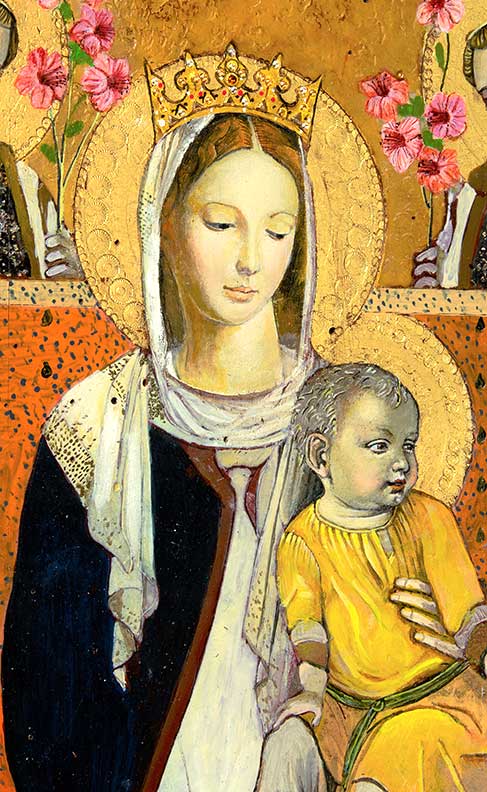

Above the head of Christ, in the “crown” of the Cross (illustration 6) we see two miniatures: the first of them depicts Mary, Mother of God, attended to by two angels. Mary is depicted in a frontal perspective, raising her hands in a gesture of prayer, interceding for us. This image of Mary praying (orans) is characteristic of Byzantine and Romanesque art whose roots stretch as far back as ancient Christian art (painting in the catacombs), in which the figures of the saints (martyrs) were represented in a posture of prayer with hands raised. The Mother of God, praying (orans), is a personification of the Church, interceding for the world before the throne of Christ. The presence of the angels indicates the special dignity of Mary, full of grace, who by her divine maternity is “raised high above the Angels.”

A second miniature, above the round shield of Christ the “Pantokrator” (In Greek Пαντοκρατωρ – “ruler of all”), represents Him as the Ruler and Lord of the Universe. Jesus is blessing with His right hand, and in His left hand is holding the scroll of a book – the symbol of His Law. The red (purple) garments refer to the color of the imperial garments, which are also a symbol of his divine dignity. Purple and red beautifully complement each other with the dark blue background, symbolizing His humanity.

Extensions (terminals)

The miniatures on the „extensions” of the horizontal beam of the cross (illustration 12) represent the Angels who adore Jesus. They act as the guardians from the choir of Angels who accompany Jesus at His side.

When the Bible describes the glory of God, the Creator and Lord of Hosts, He is surrounded by choirs of Angels and Archangels. Jesus, true Man, who was born, suffered, died and rose from the dead in a concrete place and at a concrete time is also true God, and this is why the attributes of divinity are ascribed to Him.

The Boards (scomparto)

Under the transverse beam of the cross, in the “plaques” (illustration 13) we see the images of Mary and St. John. This is a reference from Holy Scripture: “And next to the Cross of Jesus stood his Mother and his Mother’s sister, Mary, the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene. When, therefore, Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing next to her, he said to his mother: “Woman, behold your son. And then he said to the disciple: “Behold your mother.” And from that moment he took her into his home” (John 19: 25-27).

Mary, the Mother of God, stands beneath the Cross at the right side of Jesus (looking at the Cross – in the left niche from our vantagepoint), dressed in a dark blue tunic and a brown mantle; in the other side we see St. John the Apostle, dressed in red garments.

The Base (piede - Feet/Calvary)

The main element of the composition at the “base” of the Cross (illustration 15) is Mount Gol-gotha (Greek Γολγοθα, translated into Latin as Calvaria, meaning “skull”), where the drama of the crucifixion was played out. Here we see the brown-colored rocky hill, and at its center, with a black background (the color symbolizing death and the netherworld) a white skull. In accord with Jewish tradition, the skull of Adam (in Hebrew, Gulgolet) was buried on one of the hills in the vicinity of Jerusalem, and even though the Gospel writers do not mention this tradition, ancient Christian writers such as Origen were aware of it.

The Most Precious Blood of Christ, flowing from His wounds, falls directly onto Adam’s grave (illustration 14). In this symbolic framework, a profound theological message is expressed. It is the main message of the Good News contained in the Letter of St. Peter: “After all, Christ suffered likewise for you and left you an example, so that you may follow in his footsteps. He committed no sin, nor was there any deceit on his lips. When he was mistreated, he did not fight back; when he suffered, he did not threaten, but entrusted himself to the One who judges justly. He himself bore our sins in his own body, nailing them to the tree, so that we may no longer be partakers of sin, but live for the sake of justice – by the blood of his wounds you were healed” (1 Peter 2:21-24).

At the summit of the hill stands a rooster, and on either side of it, we see two figures: St. Peter (on the left side) and a man in a white garment, holding a sword. The figure in white may be one of the servants of the High Priest or St. Paul, who often in the paintings of this time accompanies St. Peter. In support of this second hypothesis, the sword also comes into play, the instrument of St. Paul’s martyrdom. The scene alludes to St. Peter’s betrayal, when he denied three times before others that he knew Jesus.

In the Gospel according to St. John we read: “And as Simon Peter was standing by the fire to warm himself, they said to him at that time: Are you not one of his disciples? He denied it saying: I am not. One of the servants of the High Priest, a relative of the one whose ear Peter had cut off, said: Did I not see you together with him in the garden? Peter again denied it, and immediately a cock crowed” (John 18:25-27).

Some art historians suggest that the rooster, as a portent of the rising Sun, is a prophecy of the Resurrection of Christ. Its symbol is to remind us that the Crucified Jesus on the third day overcame death and “visited us, as the Rising Sun from on high, to shine on those who walk in darkness and in the shadow of death, and to guide our feet in the ways of peace” (Luke 1:778-79).

The Carmelite Charism Embedded In The Jubilee Cross

An icon does not constitute an item of decoration, but rather is meant to lead a person into the realm of the sacred, the place of meeting with God. Icons are not painted, but are “written” because they contain within themselves many codified symbols which invite us to contemplate the communication of a concrete truth of the faith.

The Jubilee Cross, which by its style is related to icons, shares all their characteristics. In order to comprehend it, it is worth recalling this fact because when the Cross was designed, we were guided not so much by aesthetic considerations or even by the canons of artistic design, but by the desire that the image would help us in prayer – so that, located in the center of our Carmelite church, it would contain in itself the message corresponding to this shrine.

During our analysis of the Romanesque church of the master of Bigallo, we already described the main message of the image: the Mystery of the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ. Because, in contrast to the history and charism of Carmel, the drama that was played out on the Cross is known well to all, the purpose of this explanation here is to describe those lesser known but no less essential elements pertaining to Carmel.

Jesus is the central figure of the icon, just as our faith and our entire life are centered on Him. The remaining elements of the Cross: the figure of the Virgin Mary as well as the angels and saints have been placed there only to help us understand the fruits of the Cross and to invite us to give a concrete response to its message. In our case, the charism of our Carmelite Order contains this message in the symbolism of the Holy Scapular, as written into the Carmelite Rule and freshly interpreted by the Spanish reformers St. Teresa of Jesus and St. John of the Cross.

In obsequio Iesu Christi vivere

The Precious Blood in the wounds of Christ flows on to Adam’s grave, symbolically making all of humanity clean (illustration 16).

Under the grave of Adam, in the figure of a cross, we see a miniature depicting Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, also commonly referred to as Our Lady of the Holy Scapular (illustration 16). It is precisely through this sign which is the Holy Scapular that we invite everyone to make their covenant with Mary, to imitate Christ in Mary’s spiritual school and to entrust themselves to her protection and intercession.

According to ancient tradition, Mary handed on this tradition to the first Carmelites through St. Simon Stock, the Superior General of the Order at that time, in Aylesford, England, during the night of July 15-16, 1251.

Pointing to the scapular, which was a part of the habit (in the form of an apron protecting the tunic from being soiled), Mary gave it a spiritual meaning, saying: “Receive, my most beloved son, the Scapular of your Order. Whoever dies wearing it will not suffer the fires of hell.”

Pope Clement VII (in the Papal bull of August 12, 1530) solemnly confirmed the privileges and promises associated with the Holy Scapular. The Holy Scapular is therefore the Carmelite way of receiving all that Christ merited for us by His Passion, Death, and Resurrection. It is, like the Holy Rosary, a sacramental, likewise defined as “spiritual armor,” so that everyone who receives the Scapular entrusts his life to Mary “in order to experience her motherly presence in the daily task of putting on our Lord Jesus Christ,” according to St. John Paul II. The heart of the Scapular devotion thus consists of committing ourselves to Christ with Mary as our model, living in union with her and imitating her virtues.

As an encouragement for us to receive the Scapular, we find the words on the beams of the Cross on each side – the words of Jesus which He addressed just before His death to His Mother and to the beloved disciple St. John: “Behold your mother” (from the Latin Ecce mater tua) and “Woman, behold your son” - in Latin: Mulier, ecce filius tuus, (illustration 34).

Located in the upper part of the miniature is the invocation: In obsequio Iesu Christi vivere (“to live in obedience to Jesus Christ”), which was taken from the first lines of the Carmelite Rule.

To the right of the Virgin Mary, we see St. Albert, Patriarch of Jerusalem (S. Albertus), the author of the Rule, which (written on parchment), is being held by St. Brocard (S. Brocardus), who is standing on the other side of the Virgin Mary. The image therefore refers to the sources of Carmelite spirituality, which flowed out from Mt. Carmel in the Holy Land at the threshold of the 11th and 12th centuries (illustrations 18-21).

Carmel means “garden” and is the name of a coastal mountain range extending over a region of about 25 kilometers, which along with its adjoining inclines stretches down to the Mediterranean Sea. Because of its abundance of rain and rich greenery, the mountain was the site for the cult of Baal, the god of fertility, with whom the prophet Elijah did battle.

Pilgrims and Crusaders established there an informal community of hermits, whose members, “imitating the holy hermit-prophet Elijah, pursued a solitary life on Mt. Carmel, and especially in its section which overlooks the city of Porphyria, today called Haifa, near the fountain of Elijah,” according to Jacob of Vitra, the Bishop of Akka.

After several years, between 1206 and 1214, the hermits petitioned St. Albert, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem (illustration 37), to have their way of life, which they had already been practicing, to be codified in a Rule of Life. This was how the short Rule of Conduct, also called the “Formula of Life,” arose, which became the primitive form of the Carmelite Rule, confirmed at last in 1226 by Pope Honorius III (illustration 20).

After the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which resulted from the bloody persecutions by the Saracens, the Carmelites had to abandon the cradle of their order on Mt. Carmel. Those who stayed behind suffered a martyr’s death. In 1238, the Order was forced to transfer to Europe (Sicily, France, and England), where the Rule was adapted to new circumstances. Pope Innocent IV approved these changes in 1247, making the life of the former hermits more like the life of the mendicant orders, such as the Franciscans and the Dominicans.

The parchment held by St. Brocard (illustration 22) is depicted employing the technology of ceramics, which is why, after the enlargement, we can clearly read on it the Latin citation from the Rule. In English translation, it sounds like the following: “In many and varied ways our holy forefathers taught that everyone, regardless of their state and chosen way of life, should live in obedience to Jesus Christ (in Latin: in obsequio Iesu Christi vivere) and serve Him faithfully with a pure heart and upright conscience.”

These first directives of the Rule indicate its universal scope, thanks to which it can inspire everyone with the words of St. Albert: “whatever his station and chosen way of life,” and this is why, to this very day, so many religious orders, associations, and communities have based their spirituality on it. To imitate Christ with Mary as our model means, above all, concern for remaining in God’s presence at all times and fulfilling His will. It means to live in constant prayer, which is nourished by God’s word, and, like Mary, “to ponder it day and night” in our hearts.

Without question, the majority of the Rule is a compi-lation of texts from Holy Scripture. A perfect example of this is the section entitled “The Spiritual Battle,” in which St. Albert encourages his brothers in this way:

“Because man’s life on earth is fraught with temptation, and those who wish to live devoutly in Christ encounter persecution, while the devil, for his part, as your adver-sary, prowls about like a roaring lion, looking for someone to devour, therefore clothe yourself in God’s armor, so that you may be able to withstand all the deceitful promptings of the enemy.

Gird your loins with the belt of chastity. Strengthen your hearts by holy meditation, for it is written: holy meditation will protect you. Place on yourself the mantle of justice, so that you may love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and all your strength, and your neighbor as yourself.

In every circumstance, take faith as your shield, thanks to which you can repel all the deadly arrows of the Evil one. Without faith, after all, you cannot be pleasing to God. Wear also on your head the helmet of salvation, so that you may await salvation from the Savior, who saves His people from their sins. The sword of the spirit, moreover, is the Word of God, which should abide abundantly on your lips and in your hearts. In all that you do, therefore, do it in accord with the Lord’s Word.”

THE CARMELITE REFORM

To reflect the history and spirituality of our Order in the place where, in accord with the dictates of Romanesque art, the images of the Virgin Mary and St. John are placed (the boards - scomparto), the figures of St. Teresa of Jesus and St. John of the Cross are presented in painting (illustration 23) The words pronounced by Christ and written at the side of the Cross: “Behold your Mother” take on a double meaning here. Referring, in the first place, to Mary and to each of us, they remind us at the same time that St. Teresa is the mother of a new branch of the Carmelite Order, (the Discalced Carmelite sisters and friars), which she initiated with the help of St. John of the Cross in 16th-century Spain.

St. Teresa of Jesus (1515 – 1582)

There is no way to convey the teaching and influence of St. Teresa (illustration 24) on the communities she founded through a single image and in a few sentences. On the Jubilee Cross, St. Teresa holds in her hand a parchment with a copy of her poem: “Nada te turbe.” “Let nothing disturb you, let nothing frighten you; all things are passing. God never changes. By patience you will obtain everything; whoever attains God, lacks nothing. God alone suffices.” These words, probably the most well known of the saint from Avila today, have been rendered on the Jubilee Cross in the original Spanish version: “Nade te turbe, nada te espante, todo se pasa, Dios no se muda. La paciencia todo lo alcanza quien a Dios tiene, nada le falta. Solo Dios basta.” The painter of the image, Leszek Maćkowiak, took additional care to ensure that this text was rendered in the style of handwriting typical of its author, St. Teresa herself (illustration 25).

In 1970, Pope Paul VI conferred on St. Teresa the lofty title of “Doctor of the Church.” What does this 16th-century nun teach us today? Just as in her time Christopher Columbus discovered for the Christian world new and unknown lands, so through St. Teresa, God invites us to embark on an interior journey, a journey into the depths of the “interior castle” of our heart. The gate to this castle is prayer, which according to the words of St. Teresa herself means “nothing other than a trusting and friendly communion with God, and poured out as many times as that conversation is carried on in solitude with Him, of Whom we know that He loves us” (The Book of her Life: 8,5).

St. Teresa is a teacher of prayer, prayer understood not only as an act of our devotion, but as an act full of trust, love and determination establishing a relationship of friendship with God. “It is not our main concern that we should meditate so much as it is that we should love much – writes St. Teresa – and therefore we should mainly act and apply ourselves to what effectively awakens us to love” (Interior Castle IV, 1, 7).

Friendship is the key to understanding the Teresian message, and because God is a personal Being, therefore prayer must also be a relationship that absorbs the entire person, his whole life. “God alone suffices,” and therefore our relationship with God cannot be just an appendage to our “normal” life, but rather is the source of the fullness of life, its content and its purpose.

St. Teresa emphasized this explicitly in writing about the three main foundations of prayer: “The first of these three elements is mutual love among ourselves. The second is complete detachment from created things. The third is true humility, which, even though I mention it last, is the main one, and contains within itself the others” (The Way of Perfection 4, 4).

St. John of the Cross (1542-1591)

In establishing the men’s branch of her Order, St. Teresa was accompanied by a friar who was much younger than her, Brother John of St. Matthias (Yepes), who on the day of the founding of the first monastery of the Discalced Carmelites in Duruelo, Spain (November 28, 1568), took the name of John of the Cross (illustrations 28, 29). Despite his young age, God granted him extraordinary spiritual wisdom and experience. For almost 20 years, he would accompany St. Teresa in establishing numerous monasteries of the Discalced Carmelite Friars and Sisters, becoming not only her spiritual son but also her confessor and trustworthy spiritual director.

Like St. Teresa, St. John of the Cross was also added to the ranks of Doctors of the Church. Today, he is considered one of the greatest Catholic mystics, not only because God unveiled His mysteries before him, but also because God gave him the gift to understand them and, through poetry and theological treatises, to make them accessible to others.

In a certain way, John became a writer out of necessity. Under the influence of “an overabundance of grace,” he wrote his own poems, which disclose his mystical experiences. Later, at the re-quest of the Discalced Carmelite sisters, his fellow friars, and people for whom he served as spiritual director, he began to write a commentary for these poems. In this way, there arose his major works: The Ascent of Mt. Carmel, The Dark Night of the Soul, The Spiritual Canticle, and The Living Flame of Love.

St. John had the custom of giving his penitents small pieces of paper or holy cards with spiritual sayings. In fact, one of these sayings can be found precisely on a piece of parchment with an image of St. John and is translated into English as follows: “At the evening of life, you will be judged by love. Learn to love God as God wishes to be loved, and leave aside your own likes and dislikes.” [Don’t concentrate on yourself]. Just as in the text on the image of St. Teresa, the words of St. John were written in his original language, following the character of writing typical of the Spanish mystic: “A la tarde te examinarán en el amor. Aprende a amar como Dios quiere ser amado y deja tu condición.” (illustration 29).

St. John was a faithful imitator of Christ. By the example of his life and writings, he communicated the truth of the Gospel, emphasizing that love unites us with God, that love of God and neighbor is the basic purpose and meaning of our life. There is nothing more important than recognizing and accepting the love revealed in Jesus Christ, and by cooperating with His grace, to make our whole life (our relations, desires, works, and aspirations) an expression of this love.

St. John did not choose the predicate “of the Cross” by accident. Suffering accompanied him from childhood and formed his spirit. He devoted much space in his treatises to the meaning of suffering in spiritual development. We cannot fail to mention his use of the term “dark night”, which he established for the needs of his teaching, and which he defined as the journey toward union with God as both the point of departure, the road, and the destination.

According to St. John’s work, The Ascent of Mt. Carmel:

“We can offer three reasons for calling this union with God a night. The first has to do with the point of departure, because individuals must deprive themselves of their appetites for worldly possessions. This denial and privation is like a night for all one’s senses. The second reason refers to the means or the road along which a person travels to this union. Now this road is faith, and for the intellect faith is also like a dark night. The third reason pertains to the destination or point of arrival, namely God. And God is also a dark night to the soul in this life. These three nights pass through a soul, or better yet, the soul passes through them in order to reach union with God.” (Ascent of Mt. Carmel, Book One, II, 1).

The Carmelite Coat-of-Arms

On the “extensions” of the arms of the Cross (above the plates with the images of the holy Spanish mystics), there are two miniatures with images of angels (illustrations 32), who by their presence emphasize the Divine dignity of Christ. By comparison with the Roman original, a slight change in these images is indicated by the presence of the Carmelite coat-of-arms. Held by the an-gels in the right hand (with the left pointing to it), it is related to the labarum, a Byzantine military legion banner.

The testimony of Eusebius of Caesarea relates the vision of the emperor Constantine the Great, who “in the twilight hours, when the sun was already beginning to set, saw with his own eyes a triumphant sign in the form of a cross from the light in the sky above the sun, with an inscription upon it saying: “By this sign you will conquer” (In hoc signo victor eris). When the emperor placed the sign of Christ (XP) on the shields and banners of his armies, he won the battle. This extraordinary event initiated the sudden development of Christianity in the entire Roman Empire.

The Cross on Mount Carmel is also an integral element of the coat-of-arms of the Carmelite Order, and this is why the message of the angels is written into the main narration of the cross. It can be summarized in the following words: Christ conquered sin and death, in Him is our salvation, and the basic goal of the Order, as well as its founders and reformers, is to live for Christ, to imitate Him, to be immersed in the Mystery of His Death and Resurrection, in order to attain salvation in the end in union with Him.

The Carmelite coat-of-arms (illustration 30) is also found on the reverse side of the Cross. We see it just below the coat-of-arms of Pope Francis (illustration 31), along with information about the artist (Leszek Maćkowiak) and the date of its completion A.D. MMXX (The Year of Our Lord 2020).

TECHNICAL NOTES

The Cross is hewn out of cedar wood and has the following dimensions: 130 inches (330.3 cm) vertically, 93 inches (236.2 cm) horizontally, and 3 ¾ inches (9.5 cm) in width. It is therefore substantially bigger than the “Roman” cross.

Regarding differences in composition, our Cross does not contain a medallion in the corona. For this reason, the icon of Christ The Pantocrator (illustration 33) was placed in the location of the image of the Virgin Mary (Mediatrix), which in turn was transferred to the base and replaced by the image of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel.

The main subject of the base is therefore not the Tomb of Adam and the denial of St. Peter, but rather the beginning of the Order on Mt. Carmel. On the plaques (underneath the arms of the Cross), in place of the classical images of Mary and St. John, are placed the Carmelite saints: Teresa of Jesus and John of the Cross. Finally, a new element is likewise the sayings, depicted in gold (the words of Jesus on the cross) and the decorations located on the side and on the reverse side of the cross (illustrations 34, 35).

All of the persons represented on the cross are named in the Latin language, and for this reason the Byzantine Christogram: IC XC, alluding to the Greek words: ΙΗΣΟΥΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Jesus Christ) has been replaced with its Latin version: IHS NAZARENVS REX IVDEORVM (illustration 36).

However, we do not know what the Latin inscription on the cross of Jesus looked like. Most likely, the letter “U” was rendered by “V,” because in the classical era, that is, at the time of Jesus, there was no distinction between u and v, as both sounds were indicated by one letter. The expression “Iudeorvm,” according to Latin grammar, should contain the diphthong “ae,” which however does not appear in the image. Such an inscription without the diphthong was typical of medieval Latin, so that we find it on all the crosses of that epoch, and this is why, using that version as a model, we chose the medieval version.

SIGNIFICANT ARTISTIC INSPIRATIONS

A person familiar with Carmel, observing our Cross, would cer-tainly recognize many Carmelite themes and even entire compositions on it which have been culled from collections of Carmelite iconographies. The miniature of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel at the base is a copy of the Carmelite Madonnas (1328) painted by Pietro Lo-renzetti (1280/85–1348), constituting an element of the polyptic representing the most important events in the history of Carmel, beginning with the Prophet Elijah up to its founding by a group of pilgrims – hermits of the Order on Mt. Carmel. The original is found in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, Italy (illustrations 17-21).

The inspiration in the painting of the image of St. Teresa was the 16th-century painting of an anonymous artist which is found in the collections of the Prado gallery in Madrid (illustration 26), imitating the previously famous works of Jose Ribera (illustration 27).

In painting the image of Christ the Pantocrator, a mosaic with the Deesis group was used as a model, which aside from Christ likewise depicts the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. As one of the most well-known Byzantine mosaics (illustration 38, 39), it came about in the second half of the 13th century and is found on the wall of the former Hagia Sophia cathedral in Constantinople (known as Istanbul, Turkey today).

TECHNIQUES EMPLOYED

In making the Cross, to the degree possible and despite the technical and financial limitations, we attempted to make use of techniques approximating those used in the times of the Master of Bigallo. Unfortunately, we do not know on what kind of wood the master from Florence painted in the 12th century. Because of its resistance to mushrooms and other parasites, royal cedar wood was specifically chosen. In the first phase of preparation for painting, the wood was soaked with impregnates and covered with Venetian clay, which was then submitted to grinding.

The blue color of the beams of the cross has a foundation of palladium, from which the effect of shining was obtained. Likewise, the inscription above the head of Jesus was also carried out from palladium, maintaining a continuous gloss, in contrast to silver, since it does not submit to atmospheric effects (illustrations 40, 41).

The gold (seashells of gold foil, in powder form or on plates) was placed using the jeweler’s technique of gold-plating on the pulment; then, it was mixed with the application of puncturing the surface, engraving, and other painting techniques at the disposal of the artist. Apart from the gold-plating, the cross was adorned with 414 discs of a mass of pearl (the decoration of the red arms) and 12 of the highest class of synthetic rubies (Jesus’s drops of blood), which emphasized the lofty style of the image (illustration 41).

As a coronation of the work, the image was submitted to processes enhancing the antique appearance (damage incurred, traces of repair, etc.). All of this cre-ates the effect that the cross seems to be covered with a centuries-old patina, making it more like the original works of the 13th century (illustrations 42, 43).

The entire cross was painted with oil, with the basic main colors specially prepared for this work. To ensure a uniform style, it was necessary to find a compromise between the way of representing the figures associated with the beginnings of the Order in the 13th century (Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, St. Albert, St. Brocard) on the one hand, and the image of the Crucified Jesus and the Carmelite Saints of the 16th century on the other. This is why in many places the Romanesque style was aban-doned by adding the effect of shadow and perspective typical of three-dimensional images.

In order to emphasize the personal, individual relationship of God to each person, the face of Christ was painted in a technique allowing us to attain the impression that the eyes and face of Je-sus are always focused directly on the person viewing the cross, regardless of the place in which he stands below the cross (illustrations 44).

In describing the image of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, we already commented on the parchment with the copy of the Rule of Carmel carved on a ceramic plate with the letters engraved with great precision.

There is the tiny gold inscription (visible only when enlarged) engraved on the book which Christ the Pantocrator is holding (illustration 45). In 8 lines, in letters with a height of 1/6 of an inch (1.5 mm) it is written: “Andrzej Jędzejczak built the Cross and sculpted its ha-los in 2019. Leszek S. Maćkowiak designed and painted it in 2019/2020.”

Jubilee Cross

appearance during individual stages of work

illustration 46

from the left: Leszek Maćkowiak, Fr. Franciszek Czaicki OCD, Andrzej Jędrzejczak

LIST OF ADDED ILLUSTRATIONS:

1. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo (13th century), Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica – Palazzo Barberini (Rome)

2. The Jubilee Cross (Munster, 2020)

3. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, Loggia del Bigallo (Florence)

4. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, The Art Institute of Chicago

5. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, Rome (detail: face of Jesus)

6. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, Rome (detail - cimasa)

7. The Master of St. Francis, the Crucified (second half of 13th century), Galleria Nazionale (Perugia)

8. The Master of St. Francis, The Crucified (second half of 13th century), Musee du Louvre, (Paris)

9. The Master of St. Francis, The Crucified (second half of the 13th century), National Gallery (London)

10. The Jubilee Cross, detail: Christ’s sash on the hips - efod

11. Outline of the Roman cross as drawn by Prof. Alice Ginaldi

12. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, Rome (detail: terminale)

13. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, Rome (detail: scomparto)

14. The Jubilee Cross, detail: The Adam’s Tomb

15. The Cross of the Master of Bigallo, Rome (detail: piede)

16. The Jubilee Cross, detail: The Precious Blood of Christ

17. The Jubilee Cross, detail: Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

18. Pietro Lorenzetti, (1328), The polyptic: The Madonna of the Carmelites, Pinacoteca Nazionale (Siena)

19. P. Lorenzetti, (1328), a section of the polyptic: The Madonna of the Carmelites, (Siena)

20. P. Lorenzetti, Papal approval of the Rule (section of the polyptic: Madonna of the Carmelites), (Siena)

21. P. Lorenzetti, The Handing Over of the Rule (a section of the polyptic: The Madonna of the Carmelites), (Siena)

22. The Jubilee Cross, detail: St. Brocard

23. The Jubilee Cross, detail - scomparto: St. Teresa of Jesus and St. John of the Cross

24. The Jubilee Cross, detail: St. Teresa of Jesus

25. The Jubilee Cross, detail: St. Teresa of Jesus

26. Santa Teresa de Jesus (artist anonymous, 17th century), Museo Nacional del Prado (Madrid)

27. Jose de Ribera, Santa Teresa de Jesus (17th century), Museo de Bellas Artes (Seville)

28. The Jubilee Cross (detail: St. John of the Cross)

29. The Jubilee Cross (detail: St. John of the Cross)

30. Coat of arms of the Discalced Carmelites

31. The Jubilee Cross, detail: The Coat-of-arms of Pope Francis

32. The Jubilee Cross, detail: an Angel, termnale – left side

33. The Jubilee Cross, detail: The image of Christ the Pantocrator

34. The Jubilee Cross, detail: decorative elements - Latin inscription

35. The Jubilee Cross, detail: decorative elements - Latin inscription

36. The Jubilee Cross (detail: Latin inscription - INRI)

37. The Jubilee Cross, detail: St. Albert, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem

38. Mosaic with Deesis group (13th century), Hagia Sophia (Istanbul)

39. Mosaic with Deesis group, Istanbul, (detail: The image of Christ, the Pantocrator)

40. The Jubilee Cross (documentation of employed techniques: palladium)

41. The Jubilee Cross (documentation of employed techniques: synthetic rubies in the Jesus’s drops of blood)

42. The Jubilee Cross (documentation of employed techniques: the gold-plating)

43. The Jubilee Cross (documentation of employed techniques: enhancing the antique appearance)

44. The Jubilee Cross (detail: the face of Christ)

45. The Jubilee Cross (detail: The Bible)

46. Artists of the Cross: Leszek Maćkowiak and Andrzej Jędzejczak

47. – 70. Jubilee Cross – appearance during individual stages of work